As one does, I was having a conversation about spicy peppers the other day and someone referenced the Scoville scale when comparing two peppers to show that the difference in hotness between them was exponential. After that though, knowing a little about how capsaicin causes us to perceive heat, I started wondering how exactly does one measure a Scoville Heat Unit (SHU)? So I looked it up and it turns out the Scoville scale is a subjective measure that relies on how diluted with water a pepper needs to be in order to not find it spicy anymore and not how much capsaicin is actually in the pepper. In other words, it’s a subjective measurement, not an objective one. There is an objective test for measuring capsaicinoid concentration now though; it’s called high-performance liquid chromatography and it was developed well after Wilbur Scovile was dead.

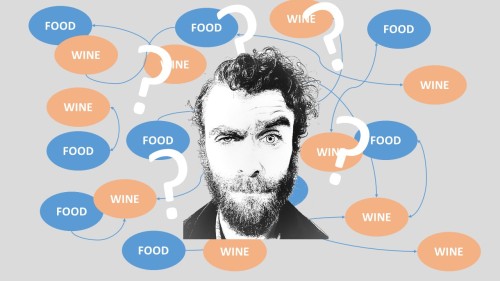

It turns out that Wilbur’s subjective test does a decent enough job of matching up with the objective one which is probably why it persists as the defacto industry scale today (or at least amongst people discussing peppers). That got me thinking about the number of of “measurements” used in wine tasting there are and just how subjective most of them really are. Some of them do a decent enough job of helping to answer questions like what’s different between these two wines or perhaps which wine you should bring to a party hosted by someone who reads too many wine magazines, but there are a lot of wine-related questions that can’t be answered by these methods…not that this has stopped people from trying. Which ones help and which ones don’t? Settle in and read on to find out.

Aroma Wheels

The science of wine aroma is beautifully (or frustratingly) complicated. Let’s take a quick trip down the process flow of how wine aromas come to be:

1.) Each grape variety has its own genotype that determines the spectrum of possible aromatic compounds the grape can develop and will have when crushed and squeezed into juice.

2.) The environment the grapes develop in which includes the climate, the weather, how the vine was trained, the soil composition, pest and disease exposure, and a whole host of other environmental factors reduce that genetic spectrum of possible aromatic compounds into what is known as the phenotype, or how the grape’s genes express themselves given the environment they develop in.

3.) How the wine is then made from the resulting grape variety or blend of varieties will not only modify the aromatic compounds in pre-fermentation grape juice, but also add in new aromas from the yeast and fermentation process as well how the wine is aged, especially if oak is used. To make things more complicated, various wine making techniques used to refine the appearance or change tactile sensations of the wine can also modify those aromatic compounds or even strip some out. Those compounds can then again be modified over time as the wine ages through slow exposure to oxygen. This is all what is desired to happen so it’s not even taking into account flaws in the process that can also modify the aromatic compounds; usually for the worse in terms of our preferences.

4.) Which aromatic compounds in the wine actually get to the olfactory receptors in our noses and throats is determined by the weights of the compounds, the temperature of the wine, the shape of the glass, the amount of oxygen that’s been infused into it through either swirling the glass, decanting, or just letting the wine sit for awhile. Compounding the complexity of these aromatic compounds are the other potential aromas coming from the food in front of you or the food you’ve already consumed wafting up from your stomach. And that’s just taking into account the olfactory receptors scattered throughout your nose, mouth, and throat. Various organs like our livers also contain olfactory receptors. Oh, and sperm does too.

5.) The receptors triggered by what we smell send signals up to olfactory bulb in our brains creating an “image” of what is being detected which may or may not change slightly based on our current state of mind or environmental cues like the color of the wine itself. Then we compare that picture with other smell “images” we have sitting in our memory banks of things we’ve smelled before to see if we can find a match.

Simple, right? [Eye-roll]

Wine professionals and amateurs alike spend a lot of time describing what a wine smells like. Back in 1984, Ann C. Noble, who is an actual sensory chemist with a PhD and who has done actual research on techniques and applications of wine tasting, developed what has become a homogenizing tool in the wine world: The Wine Aroma Wheel. The wheel contains three levels of aroma characterizations that increase with specificity as you move outward. For example, the specific aroma of “Pineapple”, which is in the third or outer-most tier, falls under the more encompassing term “Tropical Fruit” in the second-tier category, which itself falls under the general category of “Fruity” in the first-tier. This structuring of a defined set of terms was modeled on what was already being utilized for whiskey evaluations at the time. To use the wheel as it was intended as a smell-assist guide you classify what you are smelling to a category in the central or first-tier, then reclassify it into one of the possible subcategories in the middle or second-tier, and then finally reclassify it again into the outer or third-tier.

The purpose of this tool was so that people could elucidate the differences between certain wines they were in the process of discussing with someone and in that respect, it is an extremely helpful tool. But where did this list of aromas come from? Keeping in mind the process flow of how aromas get from grape to your brain, the development of this particular tool is limited primarily to the last step, #5. Dr. Noble sifted through numerous tasting notes which in all actuality are people’s subjective interpretations of what aromas are being observed as well as some actual sensory research that identified various aromatic compounds and created a refined list based on the most common descriptors used.

Now humans are pretty good sniffers, despite what some people say, and we can train ourselves to be better at identifying particular aromas. For blind tastings of wine, experts use clues, including aromas, to discern where the wine comes from. A Chardonnay from a warmer region will generally have more tropical fruit aromas if we are using the aroma wheel, and those from cooler regions tend to have more stone fruit aromas. However, this isn’t necessarily true 100% of the time, especially as wine making techniques advance and our brain/nose combo is an imperfect instrument for sussing out the actual aromatic compounds.

A more perfect instrument is a spectrophotometer. Spectrophotometry is one method for figuring out the chemical composition of a substance and it works be measuring the amount of light absorbed by a substance at different frequencies. Chemical compounds all have unique signatures that can be identified by this method without the “noise” that our human instruments can experience. While there is a massive library of these spectrophotometry signatures built, we still haven’t fully connected the presence of a cocktail of aromatic compounds (cocktails themselves in some cases) with how we will interpret them. For instance we know that Methoxypyrazines (sometimes green pepper aromas, sometimes mint, sometimes…) can be detected by humans as an aroma at 2 parts per trillion in a substance whereas Diacetyl (Buttery aromas) can be detected at 0.1 parts per million. That’s about a factorial difference and that’s not even taking into account how other aromatic compounds shape our interpretation of those aromas.

While the scientific understanding of wine isn’t there yet, some day we may be able to list out the all the aromas you could possibly smell in a wine based on the genetic code, how that grape develops, the wine making process, etc. We may even discover that there are possible aromas for a wine which no one has gotten out of a particular set of grapes thus far and we’ll develop new wine making techniques to achieve them. Until then, we’ll discuss the differences between various wines using the Wine Aroma Wheel or the number of emulators it has inspired. Just know that its only slightly more scientific than talking about what a passing cloud looks like so you should by no means restrict yourself to it or assume that someone who already knows the words on the wheel is somehow a better smell detective than you are.

Age-ability

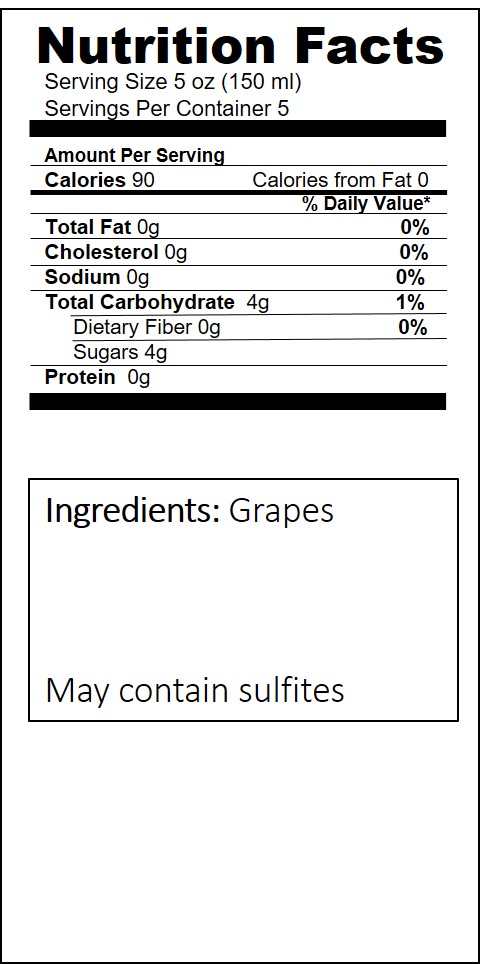

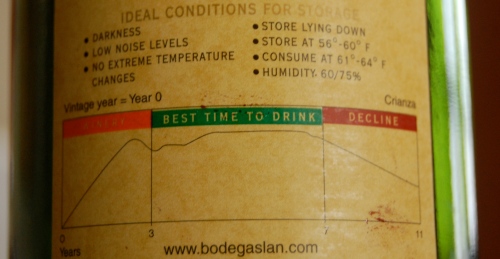

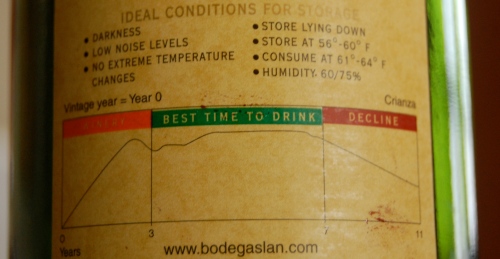

How long should you wait to drink that bottle of wine? The question is based in the adages of “Wine gets better with age” and tales of astounding vintages. The truth is that no one really knows exactly when the best time to drink a bottle of wine is. Partly, because it’s a matter of preference, but mostly because what happens when wine ages in the bottle is still somewhat of a mystery. The little we do know about wine aging is humorously depicted on the chart on the back wine label above that probably was meant to be dead serious.

The desire to age wine hasn’t actually been a big thing for wine drinkers for the bulk of the time humans have been making wine and consuming it. When humans first started making wine, it was consumed as soon as possible since we hadn’t come up with good methods to store and transport wine in. Even when we did figure out how to make heavy amphoras or light leather pouches we either didn’t stray far from the amphora or couldn’t carry much wine in our leather canteens so we consumed as much as we could until it “went bad”. It wasn’t until wine makers began adding sulfur in addition to the sulfur that occurs naturally via fermentation that we were able to keep wines for any significant period of time.

And what does it mean anyway when wine “goes bad” anyway? In general, it means one of two things: 1.) It no longer smells like healthy wine or doesn’t have much of any smell or 2.) It is in the process of turning into vinegar. The second undesirable occurrence happens when acetic acid bacteria gets into the wine. Sometimes this happens by accident or neglect and other times it happens on purpose when someone actually wants to make vinegar. The first issue though is a result of either contamination or willful oxygen exposure that has taken the wine past what I call the Point of Diminishing Maturity. In other words, the bulk of the volatile chemicals known as aromatics have been persuaded by oxygen to leave.

There are 4 factors that generally determine how long a wine can age before getting to the Point of Diminishing Maturity: Sugar, Tannins, Acid, and Alcohol which all act as preservatives in addition to the sulfur added. The simple explanation is that these factors help slow the oxidation of the wine and oxygen is what promotes the aging. The balance of those items (excluding sulfur since it shouldn’t be added at human perceivable levels) are a determination of the wine’s quality, which is separate to the question of “How long should I age this wine?” In general, the more preserving factors there are in the wine, the longer it will be able to sit in your cellar before it reaches the point of diminishing maturity. Ergo, oaked/tannic red wines will be able to age longer than most white wines, and dessert wines with lots of sugar or fortified wines will be able to age longer than anything else.

But answering the specific question of how long to age a particular wine gets a bit tricky. For red wines aged in oak, because that’s generally what people are referring to when they talk about letting a bottle sit in a cellar, the main consideration is the state of the tannins in the wine. Wine professionals usually refer to the tannins of a newly bottled red wine that was aged in oak as harsh. For older wines, they generally refer to the tannins as being soft. Those observations are unfortunately about the extent of where the scientific knowledge of what’s happening when a wine ages (and I just checked the Third Edition of the Wine Science Principles and Applications text book on that one).

There are a variety of different types of tannins and depending on the types and sizes of them in the wine they will feel differently in your mouth. Just in terms of oak aging, a professional taster can usually tell the difference between a wine aged in American oak and one aged in French oak. Acid, proteins, and a whole host of other chemicals can have an effect on tannins over time. To what extent and what types of effects are largely unknown at this point, but we do know that some tannins do in fact breakdown over time which could be one of the causes of why the tannins in an aged wine appear “soft”.

The other aspect of an aged wine is that it tends to lose it’s brighter fruit (or lighter weight) characteristics over time because of oxygen exposure. Eventually, the heavier fruit characteristics and earthy tones will go by way of oxygen exposure too, but how long that will take is highly variable and it’s something you find out after the fact. Right now, answering the question of “When will this wine taste best?” can only be answered retrospectively, despite the number of wine professionals that attempt to make predictions. However, wine professional estimates based on their collective experiences of tasting wines of different vintages is the best information we have to go on to answer the more general question that we should be asking: “What’s the maximum amount of time I should let this wine sit before I uncork it?”

To answer that, I would tell you to drink the wine within a few years of buying it off the shelf. The vast majority of wines made, and I do mean vast, especially if you’re spending under $30, are intended to be consumed immediately upon purchase. If the wine maker thinks the wine would be best if it sat for 5-10 years first because of the amount of oak aging, it’s good to listen to them. They’ve been tasting their own wines for years, including the ones that have been aging and they want you to taste their wine as they intended so even if they put it in a stupid chart like above, they are a trustworthy source. But aging wines after 10 years is where things get even trickier. Some wines aged beyond 10 years will still be lively and fruity, some will be boring, some will be contaminated with bacteria, some will be complex and mesmerizing, but the fact is, no one can accurately predict how an aged wine will fare. It can be an intellectual treat to drink older wines to see how they turned out, but don’t for one second expect them all to match up with your preferences as to what you think is good.

Tannin Scale

The Tannin Scale, or more accurately, the Total Polyphenol Index (TPI) is an actual scientific measurement that a wine lab can provide for a wine producer. Some wine producers are including it in their vintage statistics and from that perspective, it’s actually interesting to take a look at over time alongside other harvest information like Brix and Total Acidity (TA). In fact, these numbers are much of the basis behind those Vintage Charts that have been losing relevancy in modern times, but more on those later. Why the Tannin Scale has made this list, despite it being actually based in science, is that some professional wine tasters are now using the TPI score in their assessments as if it has some relevancy as to how someone will perceive the tannins in a wine.

Let’s get one thing clear: All tannins are polyphenols, but not all polyphenols are tannins. Scroll through this to see an incomplete list of polyphenols in wine (there will be a lot of scrolling). Generally, when actively tasting wines (as opposed to just drinking them) the amount of tannins will be rated on a Low-Medium-High scale. There aren’t actual measurements to this scale, it’s just a subjective assessment based on the range of wines you’ve already had. In other words, it takes experience to assess how much tannin is in the particular wine being tasted in relation to other wines. The range of the scale is based on what the individual has tasted in the past. The tricky thing about tannin perception (the “cotton-mouth” feeling you get caused by tannins binding to saliva molecules) is that it changes based on the types of tannins and their state in a wine and other factors such as acidity and sweetness…or if you’re eating, the salt or acid on your food.

Given that the total volume of tannins is only a fraction of the TPI and given that the perception of tannins in a wine is dependent on a variety of factors besides the total volume, knowing the TPI is essentially worthless.

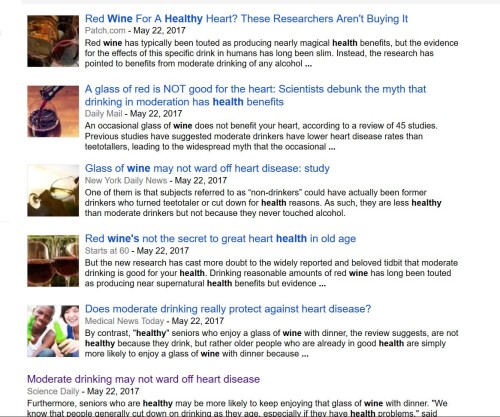

Wine (100-pt) Scores

I’m going to be upfront here and just let you know that I don’t know what goes into calculating the ratings given out by wine quality “authorities” like Robert Parker and Wine Spectator. Their methodologies are proprietary so only those who do the calculating know how they are totaled up. They may have developed some top secret techniques, heavily based in scientific reasoning, to objectively calculate their scores. They may also just be throwing darts at a board with numbers on it. However, there is certainly evidence that throwing darts may be a more accurate assessment than an objective assessment.

For instance, the same wines generally have different ratings based on who is rating them. Scroll through these Riojas and check out the scores listed. Usually the variations aren’t wildly different: a one or two point difference on a 100-pt scale doesn’t seem too significant. However, once you factor in that no one has really heard of a wine being rated below a 60 and no one really publishes a score below an 80, a point or two is more statistically significant on a 40- or even 20-point scale than the supposed 100-pt scale. Additionally, there’s some heavy speculation that certain raters have certain preferences which means the ratings are most likely better thought of as assessments of how the rater feels a wine stacks up against what they deem as “perfect” instead of an actual assessment of quality or how much you will enjoy the wine.

Vintage Chart

Vintage Charts have historically been the wine aficionado’s go-to guides when deciding what to pull out of their cellars and drink. They’ve also been deemed essential to the process of selecting a wine from a restaurant’s wine list and the memorization of them was crucial to cementing one’s status as The Highlander the one true wine lover amongst one’s friends. Now they are predominately used to help set prices for wine auctions. Vintages are always talked about in terms of what the weather was like that year and while weather is definitely a factor in how a wine will turn out it is becoming less and less relevant as wine making techniques improve.

Full vintage chart here.

Full vintage chart here.

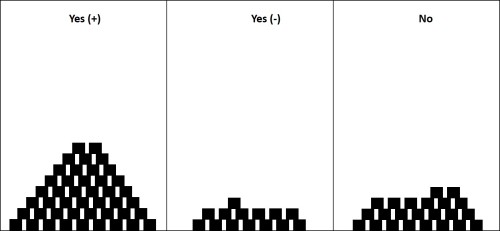

The sacrosanct irony of the wine vintage chart is that it takes all of the things I’ve listed in this post as not being overly scientific and puts them in a handy chart for you! Vintage charts are not compilations of grape quality, lab quality metrics, and tasting evaluations, they are purely the last one: tasting evaluations, and not properly samples ones. What usually happens is that a producer of a wine vintage chart will ask a few wineries in a particular region how they feel their wines are that year and then compare that to what their tasting staff is saying about what they’ve tasted and come up with their best guess as to how a wine from a particular region will be in terms of “Quality” that year. The method hardly provides what a statistician would call a good sample. Since access to previous vintage wines may prove to be difficult, it’s even more of a stretch to find a good sample of aging wines that you could accurately assess a region by. This leaves you with a chart that may be fun to look at, but it’s a bit like listening to a bunch of gossipy rumors in a high school cafeteria.

Full vintage chart

Full vintage chart